DIJ Newsletter 65, Autumn 2021

Articles

Catchwords mokushoku / mokuyoku

The COVID-19 pandemic has spawned a multitude of neologisms and fixed expressions that hardly any news report or conversation can do without. Many are related to avoiding an infection with the COVID-19 virus. While in Germany the talk is of 3G for “geimpft” (vaccinated), “getested” (tested), “genesen” (recovered) or of 2G (vaccinated, recovered), in Japan public discourse is dominated by the “three Cs” and “silence”.

Abe’s masks (アベノマスク), workation (ワーケーション), stay home (ステイホーム) – all of these terms have been on everyone’s lips in Japan since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. The masks, distributed to all households by the Abe government early on in the pandemic in 2020 and with a price tag of 26 billion Yen (216 million Euro) of public money, quickly proved to be of little use as they were too small and made of cloth. Workation and stay home also quickly lost their charm: the former usually meant work rather than vacation, and staying home all day long, often in tiny apartments, could easily feel like being imprisoned.

The Japanese linguist Yonekawa Akihiko recently explained in an article in the Yomiuri Shinbun (2 July 2021) that it was very rare “for so many new terms and buzzwords related to a social phenomenon to appear in such high density” as during the COVID-19 crisis. Even after the triple disaster of 2011 this was not the case, Yonekawa noted.

The term sanmitsu 三密 (literally: three close), which has probably been the most widespread pandemic-related term in Japan since Spring 2020, was even chosen as the word of the year. It refers to the precautionary measures that continue to be recommended, namely to avoid crowded gatherings (密集 misshū), close contacts (密接 missetsu) and closed spaces (密閉 mippei).

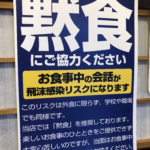

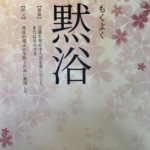

But not only keeping distance, also “remaining silent” had morphed into the golden rule during this pandemic. Today’s catchwords are requests to remain silent while eating in restaurants (黙食 mokushuko) and while bathing in an onsen (黙浴 mokuyoku). According to this author’s experience, however, neither one nor the other is followed particularly stringently, especially when several people meet to eat or bathe together. This may also be due to the fact that in Japan, even more than elsewhere, both are primarily lived and enjoyed as social activities – even and perhaps especially in crises.

Project start in quarantine and Freiburg:

Interview with Celia Spoden & David M. Malitz

We are very happy to welcome our first two new researchers since the beginning of the pandemic: Celia Spoden and David M. Malitz. While Celia has recently arrived in Tokyo, David is working from Freiburg for the time being and is looking forward to moving to Japan soon.

Where are you right now and how are you?

Celia: I have just arrived in Tokyo and I am in quarantine for two weeks. On the one hand, it’s a good way for me to familiarise myself with my new project and recover from my jet lag and the turbulent last few weeks in Hanover. On the other hand, I really want to get out. I’d like to go jogging or swimming, meet friends and really arrive in Tokyo.

David: We moved from Bangkok to Freiburg at the beginning of August and we are looking forward to going to Japan at the end of the year. In the meantime, I’m working my way into my new project. I am also teaching a course on modern Thailand at Freiburg University. After several years in Bangkok, we are happy about the autumn weather here in Freiburg.

When was the last time you were in Tokyo and what was the occasion?

David: In the summer of 2019, I gave lectures in Thai Studies at Waseda University and Osaka University – and spent a week with my family in Kyoto. Unfortunately, I was unable to take up a Japan Foundation Short-term Fellowship in summer 2020 due to the pandemic.

Celia: For me, it was even longer ago. I was a guest researcher at the DIJ at the beginning of 2018. At the time, I had a travel grant from Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, mainly for literature research for my project on the possibilities of social participation for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

What annoys you most about the pandemic?

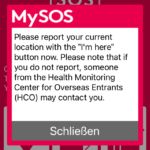

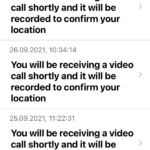

Celia: The travel restrictions and the unexpected complications that came with it. They cost me a lot of nerves and made things difficult in the last few weeks when I moved to Tokyo. In Hanover, I had to contact several test centres until I found one that would fill out the MHLW’s COVID form for me. Getting a visa also involved a lot more effort than usual. In Tokyo, I am not yet able to look for a flat. I am temporarily staying in an Airbnb flat. Getting from the airport to the quarantine flat wasn’t easy either because I didn’t know the difference between a taxi, which I’m not allowed to use, and a hired car, which I am allowed to use. Now in quarantine I have to report my health status daily, send my GPS location and usually get a video call. It is annoying because it’s an invasion into my privacy. I’m looking forward to deleting the apps in a few days.

And how has the pandemic affected you?

David: In Thailand, the authorities responded to the pandemic quickly and decisively in early 2020 – but unfortunately this did not prevent strong third and fourth waves. Libraries and archives were closed repeatedly and for a long time. And homeschooling also required additional parental involvement.

What are you looking forward to most in your first weeks in Tokyo and at the DIJ?

David: I am looking forward to getting my hands on Japanese sources again. They were inaccessible to me for a long time. And I look forward to meeting new colleagues and reuniting with old acquaintances.

Celia: For me, too: seeing many familiar faces again and meeting friends. And eating delicious food!

How would you explain your new research project to a layperson in just one sentence?

David: I want to explore how Japan has contributed to and influenced “health infrastructures” in Southeast Asia, both in the historical development of institutions and their cultural structures.

Celia: My project is about digital technologies such as avatars that enable people to work who cannot leave the house due to physical limitations; I will investigate whether these developments bring new freedoms and risks such as new forms of social exclusion or an obligation to work and a reduction of social benefits.

Which three hashtags would best describe your research projects?

Celia: #telework, #cyberphysicalspaces, #society5.0

David: #Japan, #ASEAN, #healthinfrastructures

Would you mind sharing with us your favourite place in Japan that you want to visit as soon as possible?

David: Ama-no-Hashidate in Kyoto Prefecture, but not before spring.

Celia: Oh, there are several. I lived in Kichijoji/Inokashira for a while. There are many places there like cafes, restaurants, izakayas and of course the park where I will go once the quarantine is over. Another favourite place is Okinawa. I studied there and would like to visit friends there as soon as possible.

Interview by Torsten Weber.