DIJ Newsletter 77, Autumn 2024

Articles

Catchword ōbā-tsūrizumu

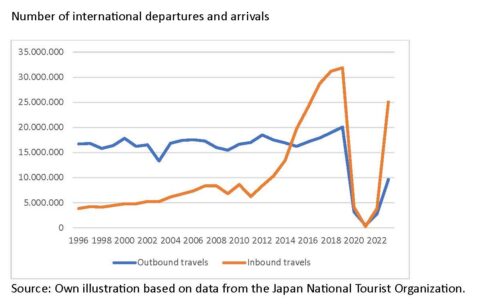

More is not always better. Following the lifting of coronavirus-related entry restrictions in autumn 2022 and fuelled by the cheap yen, inbound tourism to Japan rapidly increased over the last two years. Although the figures for 2023 were still well below the 2019 level (see chart), a new record is emerging for 2024. By July, 60% more visitors than in the same period last year had flocked into the country. As before the pandemic, by far the most tourists were from Asia. However, while more than a third came from mainland China in 2019, it was only 12% in 2023. The gap was filled by visitors from South Korea. China has since caught up. In July 2024, it retook its first place among the regions of origin.

The tourist-boom generated revenues of 5.4 trillion yen in 2023, contributing 0.9% to gross domestic expenditure.[1] This is a very positive development in view of Japan’s demographically induced weak growth. However, there are also problems. The flow of visitors is not evenly distributed over space and time and, in many places, Japan’s infrastructure is not prepared for peaks in demand. A survey by the consulting firm EY revealed that 70% of the population are not opposed to tourism but 50% feel that there is ‘overtourism’ (ōbā-tsūrizumu), particularly in Kyoto, Tokyo and Nara. The manners of some of the visitors seem to be more of a problem than the overload of infrastructure. The EY report also proposes several countermeasures that are already in use at popular tourist places around the world: Additional charges or higher entrance fees, restrictions on bed capacity and the introduction of reservation systems to regulate tourist numbers.

In comparison, Japan still seems to have room for more visitors. The 25 million tourists in 2023 are significantly fewer in proportion to the country’s 124 million inhabitants when compared to the 35 million tourists in Germany, which are spread over a population of 84 million, or the 100 million tourists that 68 million French people had to cope with in 2023. Japan’s island location and the largely mountainous and inaccessible land areas certainly constrain its capacity for accommodating visitors. Nevertheless, tourism will continue to play an important role, especially for regions outside the urban centres. Japan’s attractiveness as tourist destination will also have a positive impact on the country’s soft power, especially in Asia.

[1] Own calculations based on the balance of payments statistics of the Bank of Japan and the national accounts of the Cabinet Office.

In Memory of Kiyonari Tadao (1933-2024)

On July 23, 2024, well-known Japanese economist Kiyonari Tadao 清成忠男 passed away in Tokyo at the age of 91. He was Professor of Business Administration at the Faculty of Economics at Hosei University in Tokyo since 1972, of which he also served as a President from 1996 to 2005. He then served as an advisor to subsequent presidents. Kiyonari has immensely promoted Japanese business administration in research and teaching, furthermore he also achieved a great deal in economic policy (promotion of SMEs and regional development). His connection with the DIJ since its foundation, however, is less well known.

Kiyonari developed a great interest in Germany during his studies at the Faculty of Economics at the University of Tokyo, probably under the influence of two of his teachers, the well-known Weberian Otsuka Hisao and Matsuda Tomoo, who represented the economic history of Central Europe (later founding rector of the University of Library and Information Science Tsukuba and director of the Japanese Cultural Institute in Cologne). In contrast to these two, Kiyonari shifted the focus of his research to business administration, particularly in contemporary south-western Germany. Right up to the time when he took on important and time-consuming positions in the Japanese economy and at Hosei University, he regularly spent his summer vacation in Bonn at the Institute for SME Research, but without ever making contact with the Japanese Studies department there. As far as I remember, his contact person was Prof. Wolfgang Freiherr von Marschall.

As Kiyonari had neither applied for DAAD scholarships nor was he sponsored by the Humboldt Foundation, he was not on the radar of the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany. Receptions and parties were not his cup of tea anyway. For this reason, Kiyonari’s name was probably not mentioned in connection with the founding of the DIJ, for example as a member of the advisory board. My personal acquaintance with him was limited to a few, rather chance meetings at Matsuda Tomoo’s house, but at that time our research areas were too far apart for these contacts to have developed any further.

After the DIJ was founded in the fall of 1988, the question of access to larger libraries for our academic staff immediately arose. In view of the limited space and budget, the establishment of our own comprehensive and necessarily interdisciplinary institute library was out of the question. The university libraries, which are usually inaccessible to non-members of a university, remained hostile, but Hosei University opened its library at the main Ichigaya campus, just a few steps from the DIJ’s headquarters at the time, and was willing, through Kiyonari’s mediation, to let us into the heart of its book collections at any time. Kiyonari also advised the DIJ to apply for membership of the Association of Japanese Specialized Libraries, citing our unique focus on collecting German-language Japanese literature. This in turn meant (and still means) unhindered access for the DIJ to material collections that are otherwise hardly open to the public.

But Kiyonari’s support of the DIJ went even further. In 1992, to mark the twentieth anniversary of Okinawa’s return to Japan, the DIJ organized an exhibition of Ryukyu art and handicrafts in European museums (first and foremost Berlin) at the Urasoe City Art Museum, which was actively supported by Okinawa’s business organizations. In his interest in the development of small and medium-sized businesses, Kiyonari was particularly concerned with regional promotion. This resulted in his work in the public law foundation “Okinawa Foundation” 沖縄財団 (later 沖縄協会), which was established by the Japanese cabinet in 1972 and of which he was president from 2006 to 2016. This resulted in a fruitful collaboration for both sides, which culminated in a symposium in Naha at the headquarters of the Bank of the Ryukyus in July 1994, which was published as 東アジア経済圏における九州・沖縄 “Kyushu and Okinawa in the East Asian Economic Area” in 1995, edited by Kiyonari, Yada Toshifumi (then Kyushu University) and Kreiner, published in 1995 by Hirugi-sha, Naha, Okinawa. This was translated in part by DIJ staff members Martin Hemmert and Ralph Lützeler, and published as Economic Integration and Regional Development in East Asia – Examining the Example of Kyūshū and Okinawa (in German; DIJ Miscellanea, Vol. 11)

As President of Hosei University, Kiyonari caused a sensation when he led Hosei as the only private university among ten universities selected by the Ministry to establish a COE Center of Excellence for the first time in 2000 and established the Hosei Institute for International Japanese Studies (HIJAS), emphasizing interdisciplinarity. It remains to be seen to what extent his experience with the DIJ was decisive in this project. The contacts did not break off, as an international symposium at HIJAS in March 2008 showed, at which the groundbreaking work of the second of Siebold’s son, Heinrich (Henry), was discussed for the first time comprehensively. The DIJ’s Siebold exhibition at the Edo Tokyo Museum of the City of Tokyo at the beginning of 1996 was also groundbreaking in this respect.

In a sense, Hosei University took over the focus on museums after the change of director at the DIJ, when Japan collections and their research no longer remained a focus at the DIJ. Once again, as advisor to the rector at Hosei, in 2010 Kiyonari was able to successfully place HIJAS in 2010 among more than one hundred applications and only three approved major projects (alongside Kyushu and Kobe Universities) for international cooperation between universities and museums in the context of Japanese studies. The work on holdings of Buddhist art from Japan in European museums was carried out jointly with Japanese Studies at Zurich University and is partly available as a JBAE database.

It is therefore fair to say that Kiyonari, Hosei and the DIJ can look back on a fruitful collaboration.

Josef Kreiner is professor emeritus at the University of Bonn and founding director of the DIJ