DIJ Newsletter 73, Autumn 2023

Articles

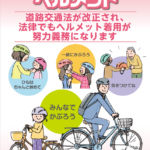

Catchword doryoku gimu

The term “doryoku gimu” 努力義務 is not new, but it always confuses a person prejudiced by a German understanding of law. This time, the introduction of mandatory helmets for cyclists on 1 April 2023 provided a new occasion to reflect on the term. In fact, the expression “mandatory helmets” is already imprecisely formulated. There is no obligation as such (“gimu”), but only the obligation to make an effort (“doryoku”). How is this to be understood? Imagine a policeman stopping a helmetless cyclist and informing her of the new legal situation. The cyclist then explains that she has made an effort. But what does that mean? Not found a suitable helmet, a scalp allergy, not enough money, no time? No, it won’t come to that, because “doryoku gimu” is a regulation without sanctions, so-called soft law, simply a request to behave sensibly. This fits the image of the Japanese state, which is reluctant to use its monopoly on the use of force. Instead, it relies on the understanding of its population and, not least, on social pressure. However, this does not always work. Since the introduction of the new regulation, only a few people, apart from the police, who now wear helmets when riding bicycles, make a visible effort to comply.

Japan’s soft use of executive power can be found in many regulatory areas. In antitrust law, for example, illegal cartels had only been sanctioned with a public reprimand until fines were finally introduced in 1977. In gender equality policy, the spirit of “doryoku gimu” also dominated for a long time instead of legal quota regulations or bans on discrimination, as DIJ alumnus Dan Tidten wrote in 2012 in his book Inter Pares. Equality-Oriented Policies in Japan (DIJ Monograph Series, vol. 50). The Japanese government’s rather soft measures in the Coronavirus pandemic also fit in here. US legal scholar John Own Haley argues in Authority Without Power (Oxford University Press 1991) that the absence of strict sanctions in Japan goes back a long way historically and is possible because of consensus-based informal social control mechanisms.

But Japan’s executive branch can also do otherwise. Five years ago, the former CEO of Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, Carlos Ghosn, was to learn this. For accusations of concealing income and embezzling corporate funds, he found himself in the mills of Japan’s public prosecutor’s office in November 2018. Driven by fear of an unfair trial and a draconian sentence, he spectacularly managed to flee to Lebanon in December 2019, one of the three countries besides Brazil and France where he holds citizenship.