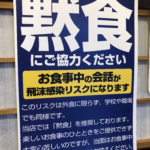

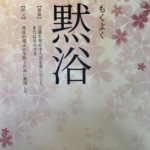

Photos below right: Posters recommending ‘silent eating’ (mokushoku) and ‘silent bathing’ (mokushoku) to avoid the risk of droplet infection. The mokushoku poster in a restaurant asks customers to refrain from talking during their meal. Imitating the style of an entry in a typical Japanese dictionary, the mokuyoku poster in an onsen provides the reading of the term, explains its meaning, and gives an example sentence: “I have taken a bath silently to avoid spreading droplets.”

Photos © Torsten Weber

Catchwords mokushoku / mokuyoku

2021年10月7日, by Torsten Weber

The COVID-19 pandemic has spawned a multitude of neologisms and fixed expressions that hardly any news report or conversation can do without. Many are related to avoiding an infection with the COVID-19 virus. While in Germany the talk is of 3G for “geimpft” (vaccinated), “getested” (tested), “genesen” (recovered) or of 2G (vaccinated, recovered), in Japan public discourse is dominated by the “three Cs” and “silence”.

Abe’s masks (アベノマスク), workation (ワーケーション), stay home (ステイホーム) – all of these terms have been on everyone’s lips in Japan since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. The masks, distributed to all households by the Abe government early on in the pandemic in 2020 and with a price tag of 26 billion Yen (216 million Euro) of public money, quickly proved to be of little use as they were too small and made of cloth. Workation and stay home also quickly lost their charm: the former usually meant work rather than vacation, and staying home all day long, often in tiny apartments, could easily feel like being imprisoned.

The Japanese linguist Yonekawa Akihiko recently explained in an article in the Yomiuri Shinbun (2 July 2021) that it was very rare “for so many new terms and buzzwords related to a social phenomenon to appear in such high density” as during the COVID-19 crisis. Even after the triple disaster of 2011 this was not the case, Yonekawa noted.

The term sanmitsu 三密 (literally: three close), which has probably been the most widespread pandemic-related term in Japan since Spring 2020, was even chosen as the word of the year. It refers to the precautionary measures that continue to be recommended, namely to avoid crowded gatherings (密集 misshū), close contacts (密接 missetsu) and closed spaces (密閉 mippei).

But not only keeping distance, also “remaining silent” had morphed into the golden rule during this pandemic. Today’s catchwords are requests to remain silent while eating in restaurants (黙食 mokushuko) and while bathing in an onsen (黙浴 mokuyoku). According to this author’s experience, however, neither one nor the other is followed particularly stringently, especially when several people meet to eat or bathe together. This may also be due to the fact that in Japan, even more than elsewhere, both are primarily lived and enjoyed as social activities – even and perhaps especially in crises.