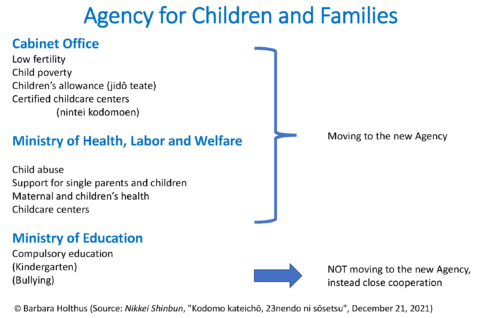

Chart below right: explanation of responsibilities according to the planned Agency for Children and Families

Catchword Kodomo Kateichō

11. April 2022, von Barbara Holthus

Japan is in the midst of a crisis regarding its future generations: the country has for decades hopelessly battled a low fertility rate; bullying in schools and on the internet is on the rise; mental health problems and suicide rates among young people are increasing; there are growing problems of child poverty, domestic violence, and child abuse. The Covid-19 pandemic’s influence on children in childcare centers and schools, both on children’s education and their social lives further intensifies the situation. Trying to tackle all of this, a joint effort by three ministries is seen as the solution. Thus on December 21, 2021, the Cabinet Office announced the formation of the Agency for Children and Families (こども家庭庁 Kodomo Kateichō) to be launched in April 2023. The publication “Basic Policy for a New Promotion System for Child Policies” lays out in detail how the ministries are to work closely together by way of the new agency.

The pandemic has intensified the need for a governmental child-centered approach, as children are a particularly vulnerable group suffering from the Covid-19 pandemic. Rates of child poverty, suicides by minors, bullying and child abuse as well the continued decline in the total fertility rate in Japan are all signs of this development.

The new Agency for Children and Families aims to tie together the governmental efforts for children by several ministries into one central agency. This agency is to streamline policies, unify governmental efforts, eliminate segmentation and thus speed up measures and break down the divisions between the different ministries (similar to the way the Digital Agency was set up) working on issues related to children. A symbolic step to underline the importance of the issue is that the agency is put directly under the Prime Minister’s office.

Social ills like bullying and child abuse are not the only focus of the policies. The fundamental policy goal, laid out in the “Basic Policy for a New Promotion System for Child Policies” is to create a child-centered society, by focusing on child well-being and by creating a sustainable society. The Policy furthermore states that parents are equally to be supported in their childrearing efforts (Cabinet Secretariat, ことも政策の新たな推進体制に関する基本方針について, December 21, 2021).

The planning and implementation of the Agency of Family and Children in April 2023 have not been conflict-free. For one, while original plans proposed by former Prime Minister Suga called for the agency to be named Agency for Children (Kodomo chō), the policy now calls for the establishment of the Agency of Family and Children (Kodomo Kateichō).

This name change is a contentious issue between the political parties, resulting in a heated debate among policy makers and the public alike. Conservative supporters of the addition of the word “family” argue that families are the foundation of children and that children grow up in families. The opponents believe that the diversity of children is undermined, as there are also children growing up outside of “families,” such as those without parents or those in foster homes (The Asahi Shinbun, „New government children’s agency to have families added to its name“, December 15, 2021; Yahoo Japan News, こども家庭庁への名称変更「戦前の家父長制を復活しようというような意図は全くない」 自民党に影響を与えたとされる高橋史朗氏が反論, December 23, 2021).

Consolidating policy making by different ministries is very difficult. This has resulted in the fact that the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) has been successfully resisting moving to the new agency; compulsory education, kindergartens, and the MEXT’s efforts regarding bullying are issues that they will cooperate with the agency about but will not allow the agency to take over completely. The fact that kindergartens will remain outside the new agency might signal the continuation of (or possibly even furthers) the split between the care of children of working parents in daycare centers (hoikuen) and those in kindergartens (yōchien). This would remain a major obstacle in the way of bridging the social class gap (see also Barbara Holthus, “Child care and work-life balance in low-fertility Japan”. In: Coulmas, Florian, Ralph Lützeler (eds). Imploding Populations in Japan and Germany. Leiden: Brill 2011).

Finally, two important questions remain, namely those of leadership and financing.

In order for the new agency to become really effective, a significant financial contribution from the central government would be needed. Yet so far, it is not fully known what fiscal support the new agency will receive. The question on who will be heading the agency also remains unanswered so far. The plan calls for a full-time ministry position. And how smoothly will the ministries cooperate? For the sake of Japan’s children, success is paramount.

Let’s hope that for the sake of Japan’s youth these ambitious plans will be smoothly implemented as to significantly improve the well-being of children and youth in the near future and support all: those rich and poor, those from single parent families and any household constellation, and those in urban and rural areas.